Our buildings

We are constantly investing in new innovative buildings, incorporating dramatic design, dynamic shape and key environmental features, creating world-class facilities for students and staff. 2016 marked the 175th Anniversary of the Young Men’s Mental Improvement Society, a predecessor institution of the University when we also began a process of renaming many of our buildings, introducing names of important figures connected to areas of the University’s work. Below you can learn about our buildings and the historic significance of their patrons.

Barbara Hepworth Building

The Barbara Hepworth Building is the home for art, design and architecture.

The University of Huddersfield has constructed a dramatically-sited, £30 million building that is the home for the study of art, design and architecture at the University. Named the Barbara Hepworth Building – after the famous West Yorkshire-born sculptor – its main frontage overlooks the picturesque Huddersfield Narrow Canal that runs through the heart of the University’s campus.

It will be the first building on a former industrial site cleared in 2016, now known as the Western Campus. The new home for the School of Art, Design and Architecture will occupy about 20% of this site, leaving some 20,000 square metres and scope for at least four more buildings as part of the University of Huddersfield’s rolling programme of development.

Learn more about the Barbara Hepworth Building or if you're interested in how it was built then please visit the project page.

Joseph Priestley Building

Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) was a chemist and a (dissenting) clergyman, but also well known for his support of the American and French revolutions and a long-standing opponent of the slave trade and religious bigotry. He was born on March 13, 1733, in Birstall, West Yorkshire.

In 1766 Priestley met Benjamin Franklin who interested him in electricity and which led Priestley to discover the conductivity of carbon and write his History and Present State of Electricity (1767). In 1767 Priestley moved to Leeds, where he lived next to a brewery and soon discovered that carbon dioxide was being formed leading to his invention of "soda water". He went on to prepare and study other gases such as nitric oxide and ammonia, collecting them over mercury which led to his greatest discovery of oxygen in 1774.

Priestley hated all oppression but by supporting the American and French revolutions and opposing religious bigotry he became an unpopular figure, particularly with the government. This led him, in 1794, to emigrate to the United States. In the USA, Priestley was revered and to commemorate his scientific achievements, the American Chemical Society named its highest honour ‘The Priestley Medal’. Priestley continued preaching in the USA. President John Adams was among those who attended his sermons and George Washington made him a welcome visitor to his home.

Picture of Joseph Priestley (line engraving by T Holloway, 1795) reproduced by kind permission of of Wellcome Images.

Ramsden Building

Opened in 1883, the Ramsden Building was the first purpose-built educational building on the University of Huddersfield campus. Edward Hughes, the architect, had been trained in the London offices of Sir Gilbert Scott, worked in the fashionable Gothic revival style. He also designed Huddersfield Market Hall, Huddersfield Bank and Spring Grove School.

The cornerstone of the building was laid by the Warden of the Worshipful Company of Clothworkers on 21 October 1881; its building costs amounted to £20,000, raised by public subscription and generously supported by grants from the Clothworkers’ Company and the Science and Art Department. The façade of the building is adorned by four lions holding shields which bear the coats of arms of the Clothworkers’ Company, Huddersfield Corporation and two major local landowners and industrialists, Sir Thomas Brooke and Sir John William Ramsden.

In July 1883 the building housed a Fine Art and Industrial Exhibition, which was opened by the Duke of Somerset. 329,639 people visited the Exhibition, among them The Duke and Duchess of Albany (The Duke was the fourth son of Queen Victoria).

Sir John Ramsden Court

Sir John Ramsden Court is one of the oldest surviving industrial buildings in Huddersfield. Described in 1778 as Mr Atkinson’s ‘new wool warehouse’, it stands alongside the Sir John Ramsden Canal, which had been authorised by an Act of Parliament in 1774 to connect Huddersfield to the River Calder at Cooper Bridge. The location is at its junction with the later Huddersfield Narrow Canal and adjacent to Aspley Basin, the port of Huddersfield.

The Ramsden family purchased the manor of Huddersfield in 1599, and this Sir John had succeeded to the title in 1769, aged 13 years.

The Sir John Ramsden Canal, as it was known, took six years to complete and cost £11,974-14s-4d, of which Sir John paid £11,500. The Canal was 3¾ miles long, had nine locks and a rise of 93 feet from Cooper Bridge to King’s Mill. It was used for traffic from 1780 onwards and enabled direct trade between Huddersfield and Hull.

The later Huddersfield Narrow Canal, built under the terms of an Act of 1794, enabled navigation via the Standedge Tunnel, to Ashton under Lyne and thence to Manchester and Liverpool.

Sir John Ramsden Court represents the entrepreneurial spirit which placed Huddersfield at the centre of the remarkable developments of the Industrial Revolution, as textile and transport technologies changed the world. Today it is home to the University’s international development office and careers staff – both areas which continue this entrepreneurial spirit in their support of Huddersfield students.

Schwann Building

Frederic and Henrietta Schwann were inspired to provide vocational education for the town of Huddersfield. In 1841 five young men employed and encouraged by Frederic set up a Young Men’s Mental Improvement Society. Together with about 30 others they then began night classes.

Henrietta was a leading light in the Female Educational Institute, one of the first of its kind in the country. Unfortunately no images of Henrietta remain in existence.

The Society was soon renamed the Mechanics’ Institute, and together the two Institutes are the direct precursors of today’s University of Huddersfield.

Charles Sikes Building

Born in Huddersfield, the son of a banker, in 1833 Charles Sikes joined the Huddersfield Banking Company. He went on to be one of the most influential bankers of his day, pioneering the introduction of the Post Office Savings Bank, forerunner of today’s NS&I, one of the UK’s largest savings organisations.

In a letter published by the Leeds Mercury newspaper in 1851, Sikes proposed the establishment of savings banks in working class organisations. He then developed the concept in a pamphlet entitled Good Times, or, The Savings Bank and the Fireside.

Existing savings banks run by local volunteer trustees were few and far between and had inconvenient opening hours, so Sikes proposed to use the burgeoning mechanics’ institutions – such as the one founded in Huddersfield in 1841, the precursor to this University – as branches of the nearest trustee savings bank. Sikes then suggested to Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Gladstone, that the Post Office should take on this role. Sikes’s proposals were controversial and were considerably revised, but were eventually accepted by Gladstone, and the Post Office Savings Bank began in 1861. By 1881 Sikes was managing director of the Huddersfield Banking Company and was knighted in recognition of his role in the creation of a scheme that, it was stated by the local newspaper, had meant “thousands of working men, women and children received their first lessons in thrift”.

Image credit; Kirklees Museums & Galleries.

Cockroft Building

Born to a cotton weaving family in Todmorden, John Cockcroft would become the best known scientist and engineer in Britain and a Nobel Prize winner.

In the 1930s, as a researcher in Cambridge, his development of what is now known as the Cockcroft-Walton particle accelerator revolutionised experimental nuclear physics, producing the first artificial splitting of the atom, the discovery of the neutron, and many other breakthroughs. By 1939 he was a professor and during WWII he made a major contribution to the improvement of radar. He was involved in the project to develop nuclear explosives, but after the war he became a leading advocate for the peaceful potential of nuclear power, founding the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell. Sir John – knighted in 1948 – was Britain’s representative at the International Atomic Energy Agency and at the conference that led to an atomic weapon test ban treaty. He presided over the development of the Rutherford High Energy Laboratory – named after his mentor Ernest Rutherford - and was involved the creation of CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research. His Nobel Prize for physics was awarded in 1951. In 1959 he became the first Master of Churchill College in Cambridge, established to improve Britain’s technical and scientific education.

Image credit; National Portrait Gallery, London

Brontë Lecture Theatres

The Brontë sisters, Charlotte (1816–1855), Emily (1818–1848), and Anne (1820–1849), are world renowned 19th century novelists. Born in a village about 12 miles north of the campus, the sisters lived much of their lives at Haworth and knew this area of West Yorkshire very well.

Like many of their contemporary female writers, they originally published their poems and novels under male pseudonyms: Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Their stories were famous for their passion and originality. Charlotte's Jane Eyre was the first to know success, while Emily's Wuthering Heights, Anne's The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and other works were later to be accepted as masterpieces of literature.

There is a particular connection to Huddersfield through Red House (built in 1660 and now a museum). It was home to a family of cloth merchants and manufacturers. Mary Taylor, who lived there, is considered an early feminist and was a close friend of Charlotte Brontë.

Charlotte Brontë's second novel, Shirley, is about the Luddite uprisings in the Yorkshire textile industry during the industrial depression of 1811-12, and much of it is set at the house.

Picture of Charlotte Bronte by JH Thompson reproduced by kind permission of the Brontë Society.

Spärck Jones Building

The development of search engines that are vital to the operation of the Internet owes a huge amount to the pioneering work of Karen Spärck Jones, who was born and received her schooling in Huddersfield.

Her mother was Norwegian – during WWII she worked for her homeland’s government-in-exile – and her English father was a chemistry lecturer. After university study in the 1950s, Karen joined the Cambridge Language Research Institute and worked on the issue of how computers could determine meaning from language. As part her work she transcribed the whole of Roget’s Thesaurus on to punched computer cards. This led to what became internationally important research in the field of information retrieval. During the 1960s – long before the dawn of the World Wide Web – she developed techniques that would later be fundamental to web-based search tools. The author of nine books and hundreds of articles, Karen Spärck Jones was a noted teacher who campaigned for more women to enter computing. She was awarded a professorship in 1999, received many honours and academic distinctions and was active in the Computer Laboratory of Cambridge University until the end of her life.

Image produced by kind permission of Markus Kuhn – University of Cambridge

Oastler Building

Hailed by his thousands of supporters as the “Factory King”, Richard Oastler (1789-1861) was an impassioned campaigner on behalf of children who were “doomed to labour from morn till night” in the mills of a rapidly industrialising Britain.

He launched his campaign in a letter headed “Slavery in Yorkshire” that was published by the Leeds Mercury in October, 1830. Oastler was a supporter of the campaigner against the slave trade, William Wilberforce, and in his public letter he compared the plight of British factory workers to the “hellish system” endured by African slaves in the Colonies. This dramatic intervention meant that he became the highly active figurehead of an important social campaign that would lead to legislation that curtailed the hours worked by both children and adults.

Between 1820 and 1838, Oastler was steward of the Fixby estate near Huddersfield, but eventually he fell out with its absentee owner. After dismissal from his post he was imprisoned for debt between 1840 and 1844. Huddersfield had been the springboard for much of Oastler’s campaigning. His legions of supporters rallied to help provide for him whilst in jail and eventually raised the money to free him. On his release on 20 February, 1844, he headed a procession of thousands who entered the town in triumph. Oastler has been much celebrated since, for example in the name of the local teacher training college which merged into what is now the University in 1970.

Haslett Building

In the early 20th century, engineering was seen as an almost exclusively male domain. Caroline Haslett made it her life’s work to alter this attitude. She was also an important campaigner for women to have greater understanding and make maximum use of electricity in the home, to lighten the burden of domestic chores.

The daughter of a Sussex railwayman, she entered the engineering industry as a secretary, but soon sought a transfer to the production side and obtained qualifications in both general and electrical engineering. In 1919, she became the first secretary of the Women’s Engineering Society, editing its journal and battling prejudice among employers and educational institutions against allowing female workers and students. When the Electrical Association for Women was founded in 1925 – in order to “popularise the domestic use of electricity” – Caroline Haslett was its secretary and the organisation rapidly grew until it had 10,000 members throughout the UK. It continued in existence until the 1980s. Her campaigning and her administrative skills earned a CBE in 1931 and a Damehood in 1947, the year in which she was appointed by the Government to the British Electricity Authority, which had oversight of the newly nationalised industry.

Image produced by kind permission of The Institution of Engineering and Technology Archives

St Paul’s

Now a public concert hall, St Paul’s was one of a number of so-called ‘Commissioners’ churches, built to serve the needs of a growing population and in response to the rise of Nonconformity. Designed by John Oates in a plain Early English style, the architect’s only extravagance was the spire.

The foundation stone was laid on 13 November 1828 and it was consecrated on 24 June 1831. John Kirk & Sons were responsible for re-ordering the internal arrangements and additions to the chancel in the 1880s. The Bishop of Wakefield preached the last service to be held at St Paul’s on 15th April 1956. Sited within the boundary of the University campus, facing Queensgate, it was leased from the Church Commissioners, for such activities as music, examinations, etc, following its de-consecration. Architects Hugh Wilson and Lewis Womersley were responsible for the restoration and conversion of the building after its purchase in 1980. It is dominated by the organ commissioned from local organ builder Philip Wood, an instrument of national significance used for examinations by the Royal College of Organists. In recent years St Paul’s has housed the University's Graduation Ceremonies.

Photo credit: Image K004271 reproduced courtesy of Kirklees Image Archive.

Harold Wilson Building

This building is named after Lord Wilson, former Prime Minister of the UK. He was born on 11 March 1916, in Cowlersley, Huddersfield. A scholarship took Harold to Oxford University, where he was a highly successful student. His exceptional skill at statistics and grasp of economics meant that during the Second World War he played an important part in the UK’s civil service, overseeing coal production. He earned admiration for his achievements in this role, but in 1945 Harold Wilson turned to politics and was elected Labour MP for Ormskirk in Lancashire, and in 1963 he became leader of the party.

At the 1964 General Election, Harold Wilson’s Labour Party won power; he was therefore Prime Minister for most of the “Swinging Sixties”, as the era of the Beatles and fashionable Britain was dubbed. Labour lost a general election in 1970, but Harold Wilson returned to power in 1974 until he stood down in 1976. He remained a backbench MP until 1983, when he accepted a life peerage and took the title Baron Wilson of Rievaulx. This commemorates the North Yorkshire abbey and lands of that name, where the Wilson family had been farmers for many generations.

Lord Wilson dominated British politics for more than a decade. Significant developments in education, civil liberties, health, housing, transport and foreign and commonwealth policy occurred during his premiership.

The Harold Wilson building was built in 1999 and is home to the School of Human and Health Sciences.

Richard Steinitz Building

Professor Richard Steinitz OBE, lecturer, composer, musicologist and author, founded Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in 1978.

He was its director for 23 years, as it grew spectacularly from an experimental weekend into an annual event of global renown, able to attract many of the world’s leading performers and composers including Berio, Cage, Boulez, Xenakis and Stockhausen. He retired from the University in 2004 (he first began lecturing in 1961), and was made Emeritus Professor, in recognition of his work which helped the Music Department establish its international reputation for contemporary composition and research. His book Explosions in November describes the first 33 years of the Festival and he is also author of the definitive work in English and Hungarian on the composer Ligeti. Compositions by Professor Steinitz have been broadcast and recorded and he has received worldwide recognition for his contribution to the promotion of new music.

Sovereign Design House

Sovereign Design House is an art gallery and a coffee house called the Toast House café; it's located on the University campus next to the Barbara Hepworth Building.

It is a grade II-listed former bath house, originally built by local firm Thomas Broadbent and Sons for their foundary workers.

At its peak, the bath house’s 16 showers catered for 120 men as they came off shift. The roof had to accommodate an enormous water tank and in the basement there was a powerful boiler. This dictated the multi-storey form of the building, but it also has design features inspired by the influential 20th century American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

The University hosted a special opening event that was attended by a number of staff from Broadbents, including former employees who had used the bath house.

Jo Cox More in Common Centre

During her maiden speech as a Member of Parliament, the late Jo Cox, focused on what binds us together as human beings rather than what divides us. The Jo Cox More in Common Centre embodies this philosophy by bringing together students, staff and visitors of all faiths in a welcoming space right at the heart of campus.

The 10,800 sq ft two-storey centre includes a community space which is used for events, activities or simply to spend some time relaxing, a congregational hall, separate male and female Muslim prayer rooms, ablution facilities, Christian and multi-faith rooms and a Chaplain’s office. Some of the University’s counselling and learning support services are also located in this contemporary and restful space.

The is the first building at the University to conform to the WELL Building Standard, achieving WELL Platinum Certification in 2024, a system which sees buildings adhere to standards for better health and wellbeing through improved air, water, light and other factors.

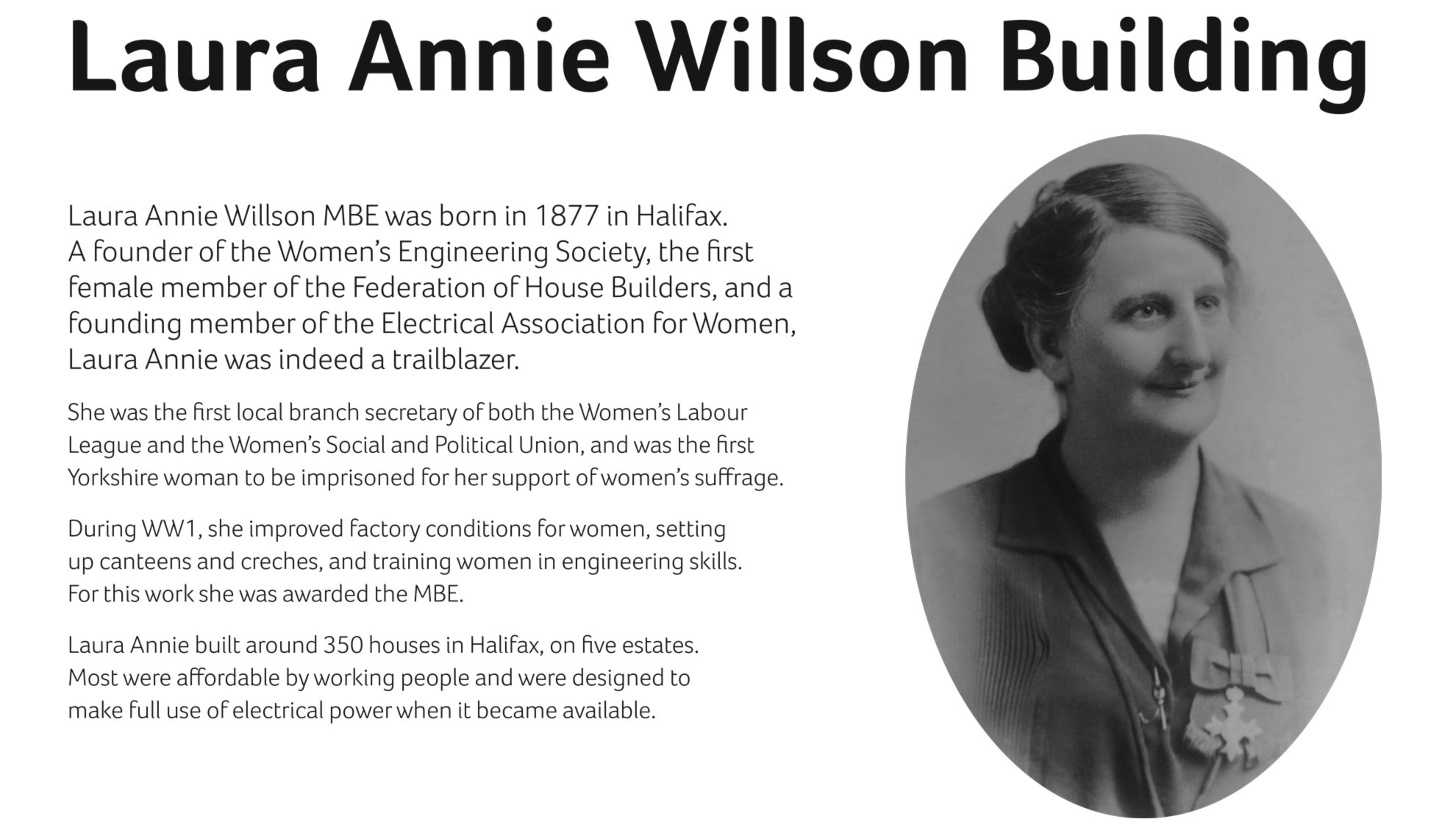

Laura Annie Willson MBE

Laura Annie Willson MBE was born in 1877 in nearby Halifax. As one of the founding members of the Women’s Engineering Society, the first female member of the Federation of House Builders, and a founding member of the Electrical Association for Women, Laura was indeed a trailblazing engineer.

As a member of the local Women’s Social and Political Union and branch secretary of the Women’s Labour League, Laura was one of the first two women in Yorkshire to be imprisoned for her political beliefs as a suffragette.

Laura’s political endeavours led to many people’s lives changing for the better. This was also the case with her work as an engineer, which included the construction of 72 houses for workers in Halifax, setting up canteens for working women, and developing housing estates that had the latest gas and electrical appliances installed.

The Laura Annie Willson Building is home to the Centre for Precision Technologies, the Institute for Railway Research and The Smart House

The University’s £22.5 million Student Central building is the hub of campus where you can find:

- iPoint – our human ‘Google’ for finding everything on campus

- The Students’ Union (SU) and SU Shop

- Student Support Services including wellbeing, disability and finance support

- Food and drink outlets

- Active Hud

- Library and computer suites

- DIGS accommodation office

- Careers Service and Job Shop